Photo: Getty

Photo: Getty Students with allergies increasingly have much more than one food to avoid. Allergic Living investigates the issues – and the solutions to create a safe and inclusive environment.

On a windy day in March three years ago, Lydia Goldfine, five months pregnant with her third child, walked hand-in-hand with her husband the three blocks to their local school in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The couple had hopes of developing a plan that would keep their eldest, Solomon, safe when he entered kindergarten in the fall. In his short life, Solomon had had anaphylactic reactions to milk, fish and mustard and he was also allergic to peanut, tree nuts and sesame. Goldfine knew this was a pivotal moment, so she had done her homework.

She knew that students with severe food allergies usually qualified for a 504 plan, the legal document that outlines accommodations to be made for a child with disabilities to allow full and equal participation at school. She downloaded resources from reliable not-for-profits, organized her wish list and her background research, and went in ready.

It was important to Goldfine that Solomon’s classroom be food-free. “Our perspective was, my child deserves the opportunity to learn in an environment where he’s not afraid, and he’s not in danger,” she says. Solomon has been taught from his first anaphylactic reaction at eight months that unfamiliar food is suspect. Sure, he might not be allergic to the Skittles used in math class. But how would a 5-year-old know a Skittle from a forbidden M&M?

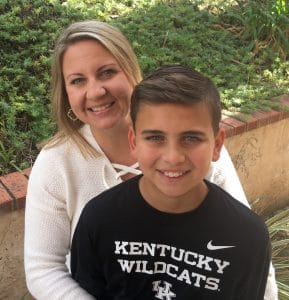

Lydia, Simon Goldfine and kids: a journey to accommodate Solomon (Superman outfit).

Lydia, Simon Goldfine and kids: a journey to accommodate Solomon (Superman outfit). Parents bringing in cupcakes to celebrate birthdays also concerned Goldfine. “Milk is his number one allergen. So Jojo shows up with cupcakes, and they’re all having a great time and they are all covered in frosting because they are 5, and there’s frosting on the chairs, on the desk, on the pencils. And then my kid has to learn in an environment that is covered in his allergen.”

When the Goldfines arrived, it felt like battle lines had already been drawn across the kidney-bean-shaped children’s table: a dozen people, including a lawyer, faced the intimidated parents. Their request for a food-free classroom was met with hostility from the kindergarten teachers. “Cupcakes are an integral part of the kinder experience,” one told her. Another wondered how she would possibly get her students to sit down for their morning circle if she couldn’t give them a Skittle.

Goldfine was flabbergasted. “I wasn’t asking them to change their curriculum. I was just asking them to change their materials.” The relationship quickly headed south. At one point, a teacher pulled them aside and told them, well-meaningly: “This school is not for you. This is not going to change, and the more times you meet, the worse it’s going to get for your kid, socially.”

In a community north of Toronto, Jyoti Parmar also struggled to find a school she felt comfortable with for her daughter, Jaya, who is allergic to dairy, eggs, peanuts and tree nuts. Now in fourth grade, Jaya is at her third school which takes many steps, such as asking parents in her class not to send spillable milk products for lunch, extra supervision at lunchtime and stringent cleaning procedures. The one problem: this school does weekly fundraiser pizza lunches, and Jaya, who also has asthma, wheezes in a room full of steaming cheese. So every pizza day, Parmar brings Jaya home for lunch, rather than having her stay at school with her friends.

“As she’s getting older, she is starting to ask, ‘Why do they do this?’” says her mom. “Why don’t they try and include me?”

Jyoti Parmar and Jaya: Struggled to find an accommodating school.

Jyoti Parmar and Jaya: Struggled to find an accommodating school. Like many families, Goldfine and Parmar are showing up at the school’s door with a new reality: their kids don’t have to strictly avoid just one allergy, they are diagnosed with multiple food allergies. A 2018 study from Northwestern University found that among children with food allergies, an astonishing 40 percent had multiple food allergies.

Tips for Managing Multiple Food Allergies at School

While many schools are accustomed to avoiding a food like peanut or even tree nuts, when you’ve got allergies to things such as wheat, milk and egg, now even craft materials and science experiments need to be scrutinized. Cafeterias too often aren’t schooled in avoiding cross-contact, and any class parties or candies given out as rewards are potential landmines.

While peanut allergy is still the biggest allergy in kids over the age of 5 and the culprit in the majority of severe reactions, Dr. Scott Sicherer, director of the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute at Mount Sinai in New York, remarks that he rarely sees kids today in his clinic with just one food allergy.

At a time when kids are having severe reactions to the Top 9 allergens and beyond, the peanut-free table alone seems a solution past its prime, nor will it pass muster in many 504 plans. When it comes to the students with multiple allergies, schools are often struggling to grasp the unique needs of incorporating these kids into the classroom, lunch room and extracurricular activities. “We’ve come a long way in the last 10 years in that there’s a foundational understanding that peanut allergy is serious, and potentially deadly,” says Gina Clowes, a longtime food allergy educator.

“But as a parent, if you’re trying to advocate for a milk-, mustard- and sesame seed-free classroom, it’s going to be a lot harder than advocating for peanuts, or tree nuts, which is kind of understood,” says Clowes, who created the “Safe at School with Food Allergies Program.”

Of course from the school’s perspective, a rise in students with multiple allergies is just one more issue in a sea of competing priorities. “There’s a lot of pressure,” says Gina Mennett Lee, a former teacher who works as a food allergy consultant to families and schools. “Teachers and administrators in the schools are feeling it,” she says. “These days, every school has to come up with a plan in case they have an active shooter; teachers are dealing with students with many medical issues, as well as those with emotional, behavioral and learning issues. Teachers are often not given the resources they need to meet these students’ needs.” As an expert observer, “I think the food allergy component just keeps getting kicked down the list of priorities.”

But a lack of awareness of multiple, severe allergies can result in reactions, and at times, severe ones. “The ultimate danger of not being aware is that we could lose someone,” says Mennett Lee. There’s another, more subtle danger of a lack of a robust food allergy policy in schools: families are left to navigate the system on their own.

This can be isolating and not every parent will be equally gifted as an advocate. Add to that poor practices, such as food allergens present in the classroom as materials, snacks or treats and now you’ve got social dynamics where children are excluded, perhaps even afraid to participate in a lesson. “That’s why we keep seeing research that supports the fact that these kids are being bullied, and that’s not decreasing as time has gone on,” says Mennett Lee.

Education Encourages Acceptance of Multiple Food Allergies

Heather Bishara (left) with son Alex.

Heather Bishara (left) with son Alex. The better news: it certainly is possible to achieve a safe and inclusive environment for a student with multiple food allergies. Just look at 14-year-old Alex, who is in 9th grade in San Diego, California. He’s allergic to wheat, egg, soy, tree nuts, peanuts and shellfish, among other things, and his mom, Heather Bishara, has made it her mission since he started preschool to make his school environment as safe for him as possible.

“I have armed Alex with table wipes, hand wipes, and food wrapped in paper towels that he can use as a placemat. I provide safe snacks for the classroom and remind Alex daily to ask the teacher to wipe down desks and wash hands if snacks are eaten. I follow this up with reminder emails and face-to-face conversations with his teacher,” she says.

Bishara, a stay-at-home mom, used to attend every elementary school party and every field trip. Last year, she accompanied an 8th grade overnight retreat to help with her son’s food. She sees herself as a partner with the teachers in keeping Alex safe. “He has not had incidents at school,” says his mother.

Across the country in the rural town of Colbert, Georgia, Oliver, a third-grader who also has high-functioning autism, has a paraprofessional with him during the day who carries his epinephrine auto-injector. The cafeteria kitchen is peanut-free, and although he doesn’t eat from it because of his other allergies to tree nuts and egg, it provides reassurance when he’s sitting next to kids with purchased lunches.

His classroom, the computer lab, speech therapy room and music room are peanut-free, and birthday celebrations have only non-food treats, or treats pre-approved by his mom, Angela Muffley. There is no food allowed on the playground and other basic prevention procedures, like handwashing, are in place.

Oliver Muffley has allergies to peanuts, eggs and tree nuts.

Oliver Muffley has allergies to peanuts, eggs and tree nuts. “This is basically unheard of in rural Georgia,” says Muffley. “There are boiled peanuts at every gas station, so to have a peanut-free cafeteria is rare.” However, Muffley was met with extreme resistance when she first approached the district about accommodations under Oliver’s individual health plan. “It felt like I was the first parent of a child to have ever had an allergy in the history of time.” She and her husband hired a lawyer, whom they consulted for advice and to understand their rights, which she credits for succeeding in getting a plan in place that she believes will keep Oliver safe.

Kristin Osborne, a disability advocate and food allergy consultant in Virginia Beach who has three children with multiple food allergies ranging from ages 7 to 17, says the awareness of food allergies has certainly improved over the years, but there are still gaps. “When my middle son was starting elementary school, it was an uphill battle to get accommodations to adequately keep him safe in school.”

In her experience, teachers have an understanding of 504 plans, but often fail to grasp a key aspect of accommodating multiple food allergies: “They didn’t fully understand that the plan was in place to make sure my child was included, not excluded.” Some teachers, for example, would bring in classroom materials that contained her sons’ allergens. “Their fix was to have him sit off to the side and watch while the others participated.”

The Osbornes: Mom Kristin says awareness has improved over the years. All three sons have multiple allergies.

The Osbornes: Mom Kristin says awareness has improved over the years. All three sons have multiple allergies. She’s seen the school system in her city significantly improve, and her own kids are now in schools that work diligently to keep them safe and accommodated. But “there are administrators who are still learning about accommodations and the need to really cater each plan to each child,” says Osborne. “Having worked with parents across the state and other parts of the country, I feel like some places are still stuck doing what they did a decade ago.”

While he agrees there are gaps, Dr. Michael Pistiner, director of food allergy advocacy, education and prevention for MassGeneral Hospital for Children’s Food Allergy Center, is optimistic about food allergy management in schools. He puts forth Massachusetts as a role model for other states: “We have many full-time school nurses in our schools. We have an amazing school nurse team with a very involved school health service unit,” says Pistiner, who is a volunteer consultant to that unit. “Massachusetts was the first to have mandated reporting of epinephrine, and also the first to have state guidelines [on food allergy protocols].”

But local success aside, he says there are many examples of communities across the United States that have good food allergy awareness, often because a school nurse or another staff member has taken the lead to coordinate and train and educate the school’s staff and community. He finds that when the groundwork with the community is done, resistance fades. “After a while, the food allergy policies really do become accepted,” Pistiner says.

The Murrieta Valley School District in California is one such community. Cathy Owens, the head nurse for the district, has been focusing on food allergies in her role ever since a 15-year-old with no known history of allergies went into anaphylaxis in her office. Owens saved his life with another student’s epinephrine auto-injector. Since then, she’s made it her task to have a safe and inclusive space for kids with allergies. Owens strongly believes good school policy targets all students, not just those with a diagnosed food allergy, and not just a specific allergen, like peanuts.

“Children have died from all different allergens, and some students’ allergens haven’t been identified. So it’s not – ‘We’re not letting this child share food.’ It’s: ‘Nobody shares food.’” Schools in Owens’ district follow a host of rules regarding food allergies: First, though it’s discouraged, any food brought into the classroom needs to be pre-approved by all parents, not just food allergy parents. Students, whether they have allergies or not, are encouraged to use paper placemats in the cafeteria, and some schools have painted lines on either all the lunchroom table tops or at least on the food allergy table. This way, students learn to keep their food within “their box.”

It’s not just about preventing reactions, though. Owens sees training staff to recognize and treat reactions as paramount, and the key to protecting all students whether they have a super-detailed 504 plan, or their allergy has yet to be diagnosed. “It’s not only recognizing that the child has a food allergy, but what do you do if there is a reaction?”

Dr. Michael Pistiner

Dr. Michael Pistiner Schools don’t need a school nurse who has witnessed an anaphylactic reaction to implement good policy, and they also don’t need to reinvent the wheel each time. As great resources, Pistiner points to both specific state guidelines and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s voluntary guidelines. The CDC document covers everything from identifying kids with food allergies, emergency training, and specific recommendations for classrooms and the cafeteria. Rather than recommending schools restrict a particular allergen, like peanut, from the premises, the guidelines recommend avoiding the use of allergens that a student is allergic to in classroom materials, and to avoid all food in parties and rewards.

“A sound policy should apply to any and all allergens and involve making sure that someone knowledgeable knows how to read a label, that people know how to prevent cross-contact, understand the concept of hidden ingredients, and can then safely feed children with food allergies and prevent cross-contact,” he says. “At the same time, they need to be able to recognize anaphylaxis, know their role in the school, and have people trained available to administer epinephrine and know what to do.”

Food allergy management is full of nuance, though, and one person’s idea of a great allergy practice – a peanut-free cafeteria table, for example – might turn another person off.

A potential danger in trying to put emphasis on more allergens than just peanut or nut is that school district allergy protocols could simply get diminished in a more complex landscape. In Canada, a major Montreal school board caused an uproar in 2017 when it rescinded its nut-free policy. Allergy advocates weren’t as troubled by the rescinding as they were with a perceived de-emphasis on allergies, and a pronouncement to end “the lunchbox police.”

While that board’s directive “encouraged” handwashing after meals and snacks, it didn’t address issues such as whether uniform anaphylaxis training would be instituted, where auto-injectors would be kept or protocols for managing treats and food rewards.

Lack of Consistency Across Districts and States

Gina Mennett Lee

Gina Mennett Lee In working with schools on food allergy management, Osborne, Clowes and Mennett Lee have all seen excellent examples of districts that “get it”. What strikes all these experts is the uneven application. “In Connecticut, I have seen lengthy, comprehensive policies and practices in place, while other towns have vague policies without written practices or regulations,” says Mennett Lee. She’s a fan of the CDC guidelines, and wishes all states would either adopt them or make their state guidelines consistent with them.

In Massachusetts, greater consistency is on the horizon, as it may soon join a handful of states that have passed laws requiring schools or districts to have extensive food allergy policies. The Massachusetts bill is among the most comprehensive; it would require schools create a policy, address prevention and emergency preparedness for managing food allergies and require staff training to implement policies. “While many Massachusetts schools are managing food allergies really well, this just takes away that variability,” says Pistiner. He hopes the law, if passed, will inspire other states to pass similar legislation.

Even with laws or better policies, each students’ individual situation needs to be looked at: What is the age of the child, and what about factors? For instance, what are the allergens and what else is the school managing – such as developmental issues or a diabetic child who requires food nearby in the class? Even with consistent policies, parents will still need to be advocates. As Goldfine found out, that is far easier when you’ve got an educated, compassionate and forward-thinking team at the other side of the table.

A week after leaving their local public school in tears, Goldfine and her husband walked into a charter school up the road, petrified. But their fears quickly diminished. This time, it was just the principal sitting across from them, and he interrupted them before they had a chance to speak. The principal kindly told the nervous parents he’d read the accommodations they’d requested, highlighted the ones the school already had in practice, underlined the things they would need to work on, and added a few more he thought would be necessary. Both Goldfine and her husband burst into tears.

Solomon is now a happy second-grader. His classmates wipe their hands and faces with supplies provided by Goldfine before they enter the food-free classroom. At recess, he eats his snack outside next to the supervisor. Lunch time is a bit more anxiety-provoking for him: he’s at the allergy table, but because he’s nervous about the other children’s milk products, he stands at the end of the table.

“Is that perfect? No,” says Goldfine. “But he’ll be fine.” The teacher, Goldfine and another food allergy parent go in once a week to wash the desks, and when ‘Jojo’s mom’ brings in cupcakes, she gives advance warning and they eat them in the cafeteria.

“Food allergy is socially treated,” says Goldfine. “You need to count on others to keep you safe.” For kids, school is the ultimate social environment. The best policies are the ones that keep them safe from physical harm as well as social and emotional harm. After all, they are just kids.

Sidebar: Tips for Managing Multiple Food Allergies at School

Web Resources

Allergicliving.com/CDCguidelines

Allerglicliving.com/middleschooltips

Allergicliving.com/504Planadvice

CDC School Allergy Guidelines

Foodallergy.org – Education Network

Foodallergyconsulting.com