Photo: Phillip Graybill / Corbis

Photo: Phillip Graybill / Corbis Too many kids and parents are consumed by food allergy anxiety. At last, mental health experts are finding answers to make allergies a

much more livable diagnosis. See also: Allergic Living’s full Food Allergy Anxiety Guide.

ANITA Law’s daughter has multiple food allergies, but Law thought she had allergy management well under control. Then in August 2013, her daughter Zoey had three anaphylactic reactions to two new food allergens in the space of two weeks. The world of this family, who live just west of Ottawa, Canada, was rocked to the core.

Six-year-old Zoey didn’t want to leave her mother’s side, and her stress levels went through the roof. It wasn’t much better for Law, who took to crying at night when her kids were asleep, worn down by the strain. Zoey’s severe anxiety led Law to leave her job for one with a shorter commute.

The girl is now 9, and daily life is still “a roller coaster” because of her anxiety about safety at school. When Zoey became immersed in playing ice hockey, it was a positive development, except that the child also said she felt “really safe” from allergen contact – since she was covered in equipment from head to toe. “I don’t think any of us truly realize just how stressed our allergic kids are, or just how stressed we are as parents,” Law says.

But researchers have become aware. There’s a growing body of published findings on the impact of food allergies on the well-being of families, with sobering results. A study from Britain in 2003 revealed that children with peanut allergy had more anxiety and a lower quality of life than children who have Type 1 diabetes and must keep a close watch on their blood glucose levels. A 2006 University of Maryland study found 41 percent of parents reporting that their child’s food allergies had a “significant impact on their stress levels.”

Northwestern University published research in 2008 that showed several allergy mothers had quit their jobs over the demands of parenting a food-allergic child, while one-quarter of parents in a 2010 Northwestern study revealed allergy-related marital tensions.

The impact of food allergies on a family is not readily apparent for those who don’t live with this disease. To the uninitiated, you simply avoid the food or foods, end of story.

Nagging Fears of Severe Reaction

The reality is that the diagnosis merely sets the table for a new life, one that comes with daily thoughts of safe food preparation and avoidance of cross-contact, often a side dish of quarrels with close relatives, some awkward socializing moments, and endless explaining to caregivers, friends, schools and restaurants. The hard slogging of precaution and avoidance can leave parents and children feeling overwhelmed, especially when they’re dealing with multiple food allergies.

Anita Law didn't realize at first how anxious her daughter Zoey had become, following three anaphylactic reactions in two weeks.

Anita Law didn't realize at first how anxious her daughter Zoey had become, following three anaphylactic reactions in two weeks. But in terms of psychological effect, the worst toll on quality of life can be summed up as this: the nagging fear that a life-threatening reaction could be a few wrong bites away. For some living with food allergies, such anxiety is maintained at a manageable level of caution, but for too many others it can tilt over into an unhealthy level of stomach-churning tension, and a diminished quality of life.

“Daily fear about an allergic reaction may be ever-present,” psychologist Linda Herbert says from her experience as director of the psychosocial clinical program with Children’s National Medical Center’s allergy and immunology division in Washington, D.C. She says some parents and children even experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder following a diagnosis or reaction.

Yet experts on the psychological impact of food allergies are aware that, for all the concern that every report of a death from a severe anaphylactic reaction brings, fatalities are still few in number and almost invariably those who have died either didn’t get the life-saving drug epinephrine at all, or did not get it immediately. Precautionary strategies coupled with emergency anaphylaxis plans do have a good track record when followed. But still – anxiety haunts this disease community.

So a huge question for allergy practices has become, not just how to test, find accurate diagnoses, and counsel food avoidance, but how to assist patients and parents so they don’t become captives to anxiety, and can learn to live well with the disease. Some large U.S. and European food allergy clinics are bringing psychologists such as Herbert on board to help families achieve that emotionally healthy state through modern techniques, which range from extremely frank discussion to wellness and cognitive behavioral approaches. Allergic Living examines some of the cases and approaches to find out: What can truly help to make the allergic life a better life?

Fears Beneath the Anxiety

When faced with a food-allergic tween with serious anxiety issues, Dr. Eyal Shemesh sometimes finds the parents have been trying to offer their child reassurance that “all is well,” and brushing fears aside. The trouble with that approach is the missed opportunity to discuss perceived dangers and send the message that it is absolutely fine to speak up about things that make you anxious.

Jennifer LeBovidge: Stress levels vary from family to family. Right, Dr. Eyal Shemesh: Candid talk with kids can work to alleviate fears.

Jennifer LeBovidge: Stress levels vary from family to family. Right, Dr. Eyal Shemesh: Candid talk with kids can work to alleviate fears. By contrast, Shemesh, a child psychiatrist and pediatrician who works with the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital, will often set out to break down the fears that have been building for a child. He might start by asking, “What are you afraid of?” and just listen as the tween details specific fears. (For example, “I am afraid I’ll have to go in an ambulance.”)

The process results in “a story of what the child is afraid of,” says Shemesh, who directs a Jaffe program called Empower (Enhancing, Managing, and Promoting Well-being and Resiliency). He then tries to provide a reality-based context. So if a child said, “I’m afraid I won’t be able to do the EpiPen,” Shemesh might reply: “Then let’s make sure you know how to use it.”

By the end of the process, the child has helped to construct a new narrative, which likely shows that many things have to go wrong for the worst outcome to happen; that adults in charge have been trained to know what to do; and that there are some easy ways to talk to friends so they can be helpful if needed. The important thing, the psychiatrist says, is to figure out what the fears are and to speak about them openly. Shemesh finds some parents are taken aback by his directness. But the kids usually get it, and respond with candid talk.

In her work with food allergy families at Boston’s Children’s Hospital food allergy program, pediatric psychologist Jennifer LeBovidge sees a range of stress – from those simply seeking ways to feel more confident about managing allergies in daily life, to those with “patterns of avoidance that go above and beyond what’s necessary for food allergy management.” Children at this end of the spectrum, says LeBovidge, may not eat lunch at school, hug friends, or touch doorknobs because they fear contact with their allergens.

In food allergy management, this is a big area of concern – called avoidance coping – which can manifest in behaviors or in the approach to diet. Shemesh gives an example of the boy who’s allergic to peanuts but who has also become nervous about eating almonds and shellfish, when there is nothing to indicate he’s allergic to such foods.

“That’s a problem,” he says, “because you begin to develop a way of looking at challenges in life as though the best thing is to run away from a scary thought.”

Helping Allergic Kids with Anxiety

In speaking with these experts, it becomes clear that managing anxiety is a process. To guard patient privacy, Herbert at Children’s National creates the composite case of a 10-year-old with avoidance coping. The boy, whom she calls Micah, is allergic to peanuts and tree nuts and, after some mild mouth symptoms, was more recently diagnosed with oral allergy syndrome to peaches and plums. With the additional diagnosis, he began refusing to eat most fruits, vegetables, crackers and breads, fearing that he was getting allergy symptoms. He stopped eating lunches his parents packed for school, and became concerned that he couldn’t safely take part in an overnight school trip.

He and Herbert discussed the difference in his two allergic conditions, and the boy allowed that it was possible that he was experiencing anxiety, not allergic reactions. The psychologist asked Micah to track when he was feeling nervous, and began teaching him relaxation methods, including deep breathing, visual imagery, and muscle relaxation. Then they moved on to problem-solving and thought-challenging techniques. They created two lists of foods (from crackers to non-pitted fruits) and food-eating locations (home, restaurants, etc.). “Then he ranked them according to how scary they were,” Herbert says.

They established an emergency action plan, and Micah began working his way up the food ladder in his sessions, first bringing foods known to be safe. He used relaxation and thought-challenging techniques, and then he would try the food, and do more relaxation.

Micah began to feel more comfortable eating these foods he’d been even avoiding at home, and started using his new techniques to try eating the safe foods in new locations. Over six months, Micah reintroduced about 10 safe foods into his diet that he had been avoiding and, after a clear plan was established, he was comfortable going on the school trip.

Working Toward Normal Life

While any severe food allergy is a significant challenge, parents of children with multiple allergic conditions face a particularly steep learning curve. Ericka Souter recalls her disbelief when her son Lex, 7, who had known allergies to peanuts, tree nuts and sesame, was also diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis or EoE. Eggs, dairy and soy were suddenly out of his diet as triggers for this allergic disease, which causes chronic inflammation in the esophagus and eating difficulty.

Souter, a contributing editor to the Mom.com website and a TV commentator, recalls thinking: “What on earth am I going to feed this child who is already underweight?” The New York mom notes, “Those allergens are in everything. It was hard for him and hard for me. There were a lot of tears.”

Jennifer Rogers of Northern Virginia, whose 10-year-old daughter Isabelle has multiple food allergies, says a “pretty normal” day for her is one “where you eat safely at home and don’t go anywhere that you have to worry about coming into contact with something that could potentially send your child to the hospital.” As Isabelle gets older, Rogers worries about maintaining physical safety and emotional balance. “You don’t want to instill a paralyzing fear in your child,” she says.

As difficult as it may seem at first, mental health experts say that it’s important from the time of diagnosis to begin to work with kids to “normalize” their food allergies, and bring down the level of stress for everyone in your home. LeBovidge uses cognitive behavioral therapy, which gets beyond mere problem-solving and looks to find the balance between vigilance and an unhealthy level of distress.

She first tells young patients to pat themselves on the back for taking precautions that keep them safe, but then they get to work on “the extra worry” that gets in the way of life. She says it’s important “to move away from worst-case thoughts to more realistic thoughts, that still employ caution.” Review of allergy facts, preparation for actions to take, and gradual but safe exposure to feared situations all help.

Role-Playing to Cut Fears

Psychologist Mary Klinnert, who works with food allergy families in the pediatrics department at National Jewish Hospital in Denver, encourages parents to pay attention to how they communicate. While serious precautions are necessary with severe allergies, she recommends discussing these with a child as a standard part of life. She would speak in a normal tone of voice – and in an age-appropriate fashion. For a younger child, the way you speak should compare to how you’d teach crossing a road or bicycle safety. When allergy precautions and carrying medication are part of daily life, this becomes accepted habit. Klinnert believes these behaviors are then more likely to be followed in the teen years.

Dr. Ruchi Gupta can relate both to the anxiety of families, and the need to normalize. She is the mother of a daughter with multiple allergies, as well as the author of several food allergy-related demographic studies. Sometimes sees herself reflected in her own “quality of life” research. One of her studies found that mothers of kids with food allergies felt the need to be continuously available to their child in case of an allergy emergency. Just like Anita Law in Ottawa, many of the mothers either changed jobs or stopped working.

Gupta, an associate professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University and Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, admits her phone is always on. “It’s always by my side. You have this fear, this anxiety all the time your child is away.” She had noticed how nervous her daughter was becoming about her allergies and began working on empowering both of them.

Gupta used role-playing for different scenarios, such as the teacher who says the class is going to have cupcakes, and helped her daughter to develop responses (such as “Excuse me, Miss Jones, but I have food allergies and can’t be around those”), and they practiced in the safety of home. “The more they repeat those words to you, the easier it is for them to do in their environment,” she says.

When looking at a food product in the grocery store, Gupta would pretend not to know if a product was safe. From an early age, she’d ask her daughter to figure it out. “Wow, you are so good at checking the ingredients and reading labels,” she’d say to instill confidence. On some occasions when her daughter’s friends are at their home, Gupta has taken the opportunity to talk frankly about food allergies, do auto-injector training, and consciously widen the safety net for her daughter. She thinks support groups online or in person are lifelines for parents feeling anxiety about allergies, and equally, she thinks kids need their own networks.

Klinnert expands on that idea, speaking of the importance of “building an umbrella of safety.” A concern she has is that people may “think” they and their child are prepared for anaphylaxis, but she has seen families’ preparation lack key elements. Examples would be: not thoroughly training every caregiver; not ensuring that what was taught was grasped; or not being comfortable with administering epinephrine.

Sometimes communication with the allergic child is less than ideal. While children will take comfort in knowing that those in charge are fully prepared, Klinnert says young patients are sometimes surprised to learn that a parent has made sure that babysitters and teachers have been fully trained on symptoms, use of epinephrine, and how to proceed if an anaphylactic emergency occurs.

Teaching Kids to Take the Lead

Age does matter in how we handle food allergies, since by 9 or 10 years of age, children are capable of making some decisions, particularly if parents have done their part to educate along the way. “Kids need to be taking increasing responsibility, working in partnership with adults, and that can only happen if kids are having new opportunities, like being able to stay overnight at a friend’s place,” says Klinnert. “lf kids are developing a sense of competence in the younger ages, and confidence as they get older, then they are comfortable telling people about their food allergies. It becomes a part of their skill set,” she says.

There’s another reason to be age aware: as children’s comprehension grows, they become far more cognizant of food-allergy related risks, including the possibility of dying of a severe reaction. Shemesh says that between ages 9 and 13, even without a clear “precipitating event,” kids can experience severe anxiety with this newfound awareness. Parents should recognize that this heightened stress can just be a normal part of development, rather than an indication of an emerging anxiety disorder.

As a parent, Shemesh says you can help by discussing the child’s feelings openly so the fears can be explored. For example, if a child says she is becoming more nervous about being exposed to foods that she’s allergic to, rather than assuring her the risk is minimal, the parent might ask what exactly the girl is afraid might happen. Then explore what can be done to minimize this concern (for instance, making sure that auto-injectors are always available). When discussion is not enough to bring a child’s growing anxiety under control, then you can seek professional help.

For those young people or parents who get anxious about using the epinephrine auto-injector, Klinnert says practice with a device trainer is helpful to build confidence. For her part, LeBovidge at Boston Children’s likes to share with young patients this new information: many children who’ve had an epinephrine shot during anaphylaxis have told her that they felt so much better so quickly. With kids who have had severe reactions, she’s careful to review what went right with the handling, of the situation, and not just what went wrong.

Well-Adjusted Attitude

Practicing a positive self-image may seem cliché, but the experts say it does impact both children and parents. It also helps to remember that food allergies aren’t the sum total of you or your child. “If you have food allergies, you are the same as anyone else, except you need to protect yourself against a few foods,” says Shemesh. “That’s it.”

He counsels kids not to think in terms of having a dreaded disease. Instead, he says, “you speak of having a manageable issue that will allow you to become as good as anyone else. You’re going to do pretty well, and you’re not limited in most of what you do.”

However, if anxiety has clearly become a family or child’s big issue, don’t hesitate to seek the counsel of a psychologist or psychiatrist with food allergy management experience. This is a challenging disease, and seeking help in such a circumstance can spare you long-running stress.

To get to that place of well-being, it’s also important to first ensure that you work with an allergist to get up-to-date, accurate medical information on your child’s allergies. In some cases, an allergist may say an oral food challenge is warranted to see if an allergy is being outgrown. Interestingly, research shows that, even when a food challenge results in an allergic reaction, the experience improves the quality of life. Shemesh has seen many families emerge from these tests more confident.

There are more positives to consider. Gupta, the prolific researcher, has another study that reveals children with food allergies are more empathetic and responsible than their peers. This backs up what Shemesh sees in his practice; that kids with food allergies may “have an advantage later in life” because they learn what it means to face adversity at a young age. “The point is to keep risk at a minimum and to learn to live with risk,” he says. Shemesh finds that “children with food allergies may grow up knowing how to face challenges in life better than their peers.”

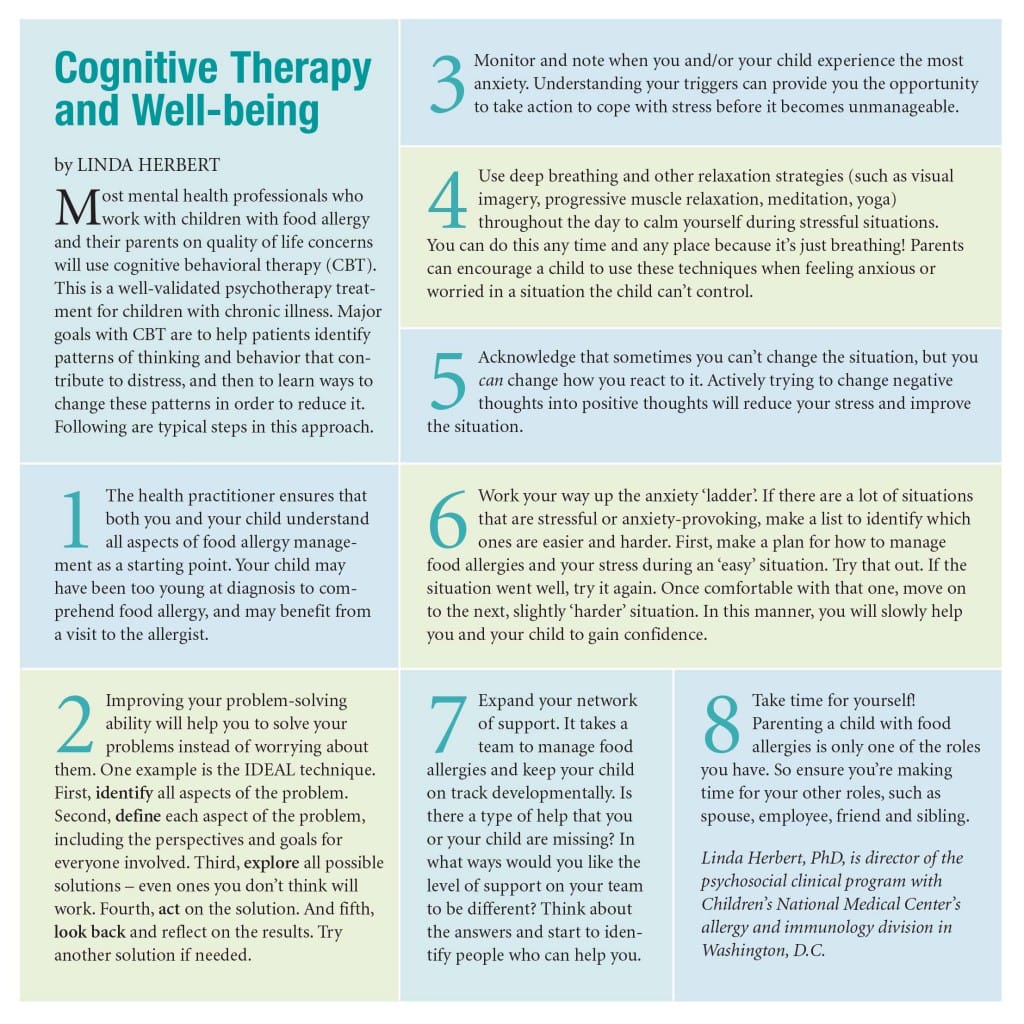

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy & Food Allergies

The following article by psychologist Linda Herbert is reproduced from the former Allergic Living print edition.