Mother-of-three Christina Casado had never heard of an epinephrine auto-injector, until the device was used to save her son’s life. The nightmare started when Andrue, who was 14 years old at the time and had no known allergies, began sampling different foods in his home economics class at his Sparks, Nevada middle school.

All of a sudden, the eighth-grade student felt his throat tighten. The teacher noticed him gasping for air and turning red. She asked if he was OK, and he barely managed to say that he couldn’t breath. The teacher quickly rushed him to the office where a nurse grabbed the school’s stock epinephrine supply and administered the auto-injector. The teen immediately took in a big gulp of air, and the school staff breathed a collective sigh of relief.

“I look at Andrue every day and I’m just so blessed that he’s still here because if it wasn’t for the stock epinephrine, he wouldn’t be,” says Casado, her eyes welling up with tears.

To her, Nevada’s stock epinephrine law, and the late Senator Debbie Smith who championed the legislation, are also blessings. The law allows schools to keep a supply of epinephrine auto-injectors on hand, without prescriptions for specific students, and to train designated school personnel to respond to anaphylaxis.

However, that law, and similar “stock epi” school laws in numerous states, are now being swept up in the price surge controversy swirling around Mylan, the distributor of the EpiPen auto-injector. Two senators have asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether contracts Mylan holds with state governments over the school programs are a violation of antitrust laws.

New York’s Attorney General is also investigating whether Mylan “may have inserted potentially anti-competitive terms into its EpiPen sales contracts” with local school systems seeking to receive a discounted price on the lifesaving devices.

Allergic Living spoke to allergy advocates to uncover their views on the Mylan fallout, and their concerns for the future of stock epinephrine programs.

Advocates Feel the Heat

For Nevada allergy blogger and advocate Caroline Moassessi, the importance of stock epinephrine first hit home when she read about Amarria Johnson. The 7-year-old had an allergic reaction to a peanut and was rushed to the office at her Virginia school, only to find that there was no epinephrine auto-injector with her name on it. Tragically, Amarria died from anaphylaxis – and since then, the little girl has become synonymous with the need for stock epinephrine that can be administered to any student with food allergies in schools.

“She could’ve been my kid,” says Moassessi, who has two children with severe allergies. “That could have been my story.”

Stories like Amarria’s are what motivated Moassessi, who is also Allergic Living magazine’s products reviewer, to gather together educators, nurses, parents, and legislators to press for stock epinephrine in Nevada.

But advocacy for stock epinephrine is now being tied to the bad press surrounding Mylan. The pharmaceutical company has come under fire due to an estimated 500 percent price surge for an EpiPen set to $600 in the United States since 2008. While the company has enhanced discount card programs and announced a less expensive generic version of its branded device, pricing of the EpiPen remains a hot button for controversy and scrutiny.

As a result, Moassessi says, “people are accusing advocates of lining people’s pockets.” She’s even seen advocates begin to question their own work. “What frustrates me is that these advocates are forgetting that legislators were listening to what everybody was saying, and then trying to choose what was best for the state,” she says.

“These laws are good. At the end of the day, if there was epinephrine in that office, Amarria Johnson probably would not be dead,” says Moassessi.

With the demands of volunteering efforts and time, some say that getting advocacy support, even from pharmaceutical companies, can be a huge help. “As far as I’m concerned, the more people we had advocating for life-saving legislation, the better,” says Connie Green, an allergy advocate who was one of the leaders of California’s stock epi lobby.

“It didn’t matter to me if it was EpiPen, Auvi-Q [an auto-injector brand currently off the market], American Lung or whoever it was who wanted to come together to help us pass this legislation.” Green’s focus was simply to ensure that epinephrine, regardless of the brand, would be available to allergic children in case of emergencies.

While every state, excluding Hawaii, allows schools to acquire their own auto-injectors, according to non-profit FARE (Food Allergy Research & Education) Nevada is one of 11 states that requires stock epinephrine. Shortly after the law was implemented in 2013, stock epinephrine saved Andrue’s life.

The teen now avoids the foods he sampled that day – avocado, tofu and blackberries. Allergy testing has been inconclusive, so he’s not certain of his exact trigger. But what he knows is that he now must always carry an auto-injector – and that an unprescribed one halted his severe reaction.

Stock Epi Vs. Stock EpiPen

At the state level, allergy advocates work with hundreds of allergy parents, politicians, educators and medical professionals to push for legislation to accommodate allergies. When Green was spreading the word about California’s 2014 stock epinephrine bill – which ended up being supported by more than 2,000 individuals – she noticed that the hashtag #EpiPenBill that was being used on social media, and expressed her concern to legislators.

She didn’t want to send the wrong message since the bill was intended to apply to any form of epinephrine auto-injector, not EpiPen exclusively. Supporters opted to use the hashtag, however, figuring that as Kleenex is to tissue, the brand’s name was synonymous with the product in general.

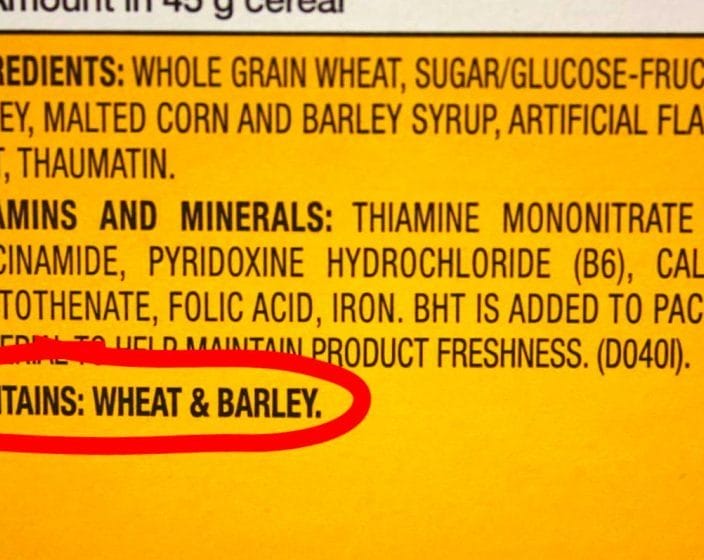

“What everyone seems to have forgotten right now is that [these bills are] for epinephrine, not EpiPen,” says Moassessi. Legislation itself only ever refers to “stock epinephrine auto-injectors,” explains Green. “It would not have passed through the first committee if there were any brand names in it.”

For its part, FARE has provided support to the stock epi grassroots initiatives by bringing local advocates together to help make lifesaving epinephrine available to those who need it. “We have always been brand-neutral in our legislative work, never advocating or recommending a particular auto-injector or manufacturer,” says Jennifer Jobrack, FARE’s senior national director of advocacy, who’s also the parent of a food-allergic child.

She points to the need for epinephrine access: independent research results showed that in Illinois alone, stock epinephrine was used 65 times in the 2014-2015 academic year. Another study found a tripling of stock epi use in New York City schools over five years.

Through its EpiPen4Schools program Mylan has distributed an estimated 700,000 free devices to more than 65,000 schools across the U.S. since inception. According to a statement from Mylan sent to Allergic Living: “Schools are eligible to receive up to four free two-packs every year, without any restrictions, and packs are refilled for free if used.” (Advocates say that some schools will also opt to purchase additional devices, which are sold at a discounted rate).

State laws allow schools to stock epinephrine auto-injectors of any brand. However, Karen Harris, president and founder of Food Allergy Kids Atlanta in Georgia says she doesn’t know of any schools that stock non-EpiPen devices. Educators have told her this uniformity is not only because Mylan offers the products at no cost, but also because EpiPen is the auto-injector most individuals are comfortable using.

Georgia’s state legislation allows, but does not require, schools to maintain a supply of stock epinephrine, and according to Harris, providing free auto-injectors has been crucial to getting schools on board. This year, despite the controversy, her state has had more requests for stock epinephrine prescriptions than ever before.

Concern for the Safety Net

With Mylan still making headlines, Shanen Sievers, one of the co-leaders of the No Nuts Moms website, wonders if she is going to start seeing frustrated parents unable to get stock epinephrine into schools, or other high-risk areas frequented by the general public such as arenas or restaurants. She worries that some advocates and legislators may shy away from all things epinephrine until the bad publicity dies down. Meanwhile, she adds: “Kids are still going to school and they won’t have that safety net.”

Those fears are top of mind for advocates like Green, who is eagerly waiting for California Governor Jerry Brown to sign a state entity bill that would allow venues such as universities, daycares and restaurants to stock any brand or generic epinephrine. “I’m almost brokenhearted already thinking that Governor Brown is not going to want to sign this legislation because he will be concerned about how it looks,” she says.

Green’s message for legislators? “Don’t confuse the controversy over the medication with the issue of saving lives and the ability to save lives, whether it’s an Auvi-Q, an EpiPen or any other auto-injector.”