Lisa Fitterman revisits the story of a young man who, as a boy, broke bones like twigs and fell into trances. We first met Eamon Murphy back in 2010. Today he has started college, is an athlete with basketball moves, and has excellent celiac disease control.

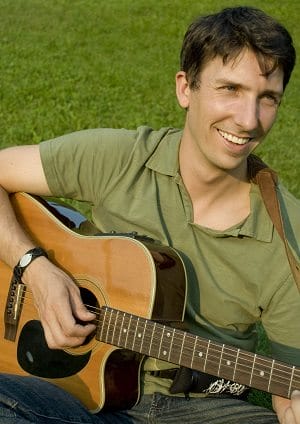

At six feet, four inches, a powerful 230-pound forward on his high school basketball team and a star student on the cusp of college, Eamon Murphy is a far cry from the little boy Allergic Living first wrote about back in 2010.

“Sometimes, I look at photos of me from when I was small and I think, ‘That was me? I think of how far I’ve come, how much I’ve grown up,” says the easygoing 18-year-old from Chappaqua, New York.

When we first met Eamon and his mom, Lisa Murphy, she related how her son had started out as an elfin toddler with a tendency to slide into disturbing trances, and whose bones seemed to break like twigs. The freaky fugue states would happen without warning – he would be playing or sitting in his car seat and all of a sudden, his blue eyes would lose focus and his mouth would move, as if he was having a conversation with a ghost. And then he’d snap back to reality.

Doctors could not explain the trances. Nor could they explain earlier developmental problems such as Eamon’s failure to track movement with his eyes as a baby, to sit up or to chew and swallow solid food. He is the youngest of four children, they noted to Lisa and her husband Bob. Eamon was accustomed to being adored and catered to, he’d catch up to his peers sooner or later.

When Lisa raised the possibility of celiac disease, which she’d been diagnosed with four years before Eamon was born, his pediatrician said it wasn’t worth screening the boy because he wasn’t bloated and didn’t have diarrhea, two of the classic symptoms.

“Don’t worry,” the parents were told. But they certainly did. Then, in 2000, Lisa attended a talk given by Dr. Peter Green, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University’s Celiac Disease Center. When she heard the leading specialist say that celiac disease is hereditary and can have a number of seemingly unrelated symptoms, and not all related to the intestines, she brought all four kids to the center to be screened.

Two of her children tested positive for the disease: Eamon, who was 4 at the time, and 11-year-old Colin who, despite his young age, was found to have undiagnosed osteoporosis in his spine and forearm. It turned out that, like their mom, the boys’ immune systems were rejecting gluten, a protein in wheat, barley and rye products, and both kids were highly deficient in iron and calcium, which are essential to bone health.

Since eliminating gluten from their diets, the two have thrived. Almost immediately after going gluten-free, Lisa says Eamon “seemed to come to life and was more focused in conversation. There was a sparkle in his eye.”

When we spoke to Eamon in April 2015, he was finishing high school and sifting through college acceptances and offers of academic scholarships. Colin, who’s 26, is a university grad who works in nearby New York City, helping to find housing for the homeless.

Because he was so young when he was diagnosed, Eamon has no memory of eating food with gluten in it. As a youngster, it took him a couple of years to catch up to his peers completely; his parents hired tutors because they knew celiac disease had impacted Eamon’s processing, speech and language skills.

Since that time, he has always been aware that he has to take responsibility for his own well-being. Eamon’s parents never made a big deal about his special dietary needs, instead treating it as second nature with a gluten-free home, and communicating the expectation that their sons would be cautious around food, read labels and make the right decisions.

When Eamon was younger, he would bring food home to his mom – pieces of birthday cake, a couple of cookies – and ask if it was OK to eat them. Now, he finds the answers about gluten content on his own. Even adolescence, often a problem period for kids who don’t want to appear different, was, if not a breeze, at least trouble-free when it came to eating.

Eamon attended high school at The Harvey School in Katonah, New York, where there is a forward-thinking approach to special diet needs. When Eamon went to other people’s homes, he’d ask questions and his friends, many of them his basketball teammates, have always understood when he couldn’t have that post-game hot dog or slice of pizza.

“I don’t feel left out,” Eamon says. “I just deal with it by eating what I can eat. If there is salad, I’ll eat salad. And in this region, I find there are usually gluten-free options of various dishes available, including pizza. I don’t think I’ve ever been glutened. At least, I haven’t felt it.”

Beyond school and athletics, Eamon loves mysteries, science fiction and fantasy, and characters like Harry Potter, the young wizard who, with his faithful friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, overcomes grievous magic obstacles to beat the bad guys.

At 18, the teenager was gearing up to leave home in the hamlet north of New York City but not too far: Boston, maybe, where his other brother runs a hotel for pets, or Scranton, Pennsylvania, or New York City. “Eamon’s birthday was last July (2014),” Lisa says. “All the kids came home and we went out for dinner. It was a big birthday but we didn’t make a big deal of it. It’s not our style.”

Still, every once in a while, Lisa and Bob, who is an oil trader for Citigroup, look at each other and shake their heads as if to say, “Remember when?” This past February, when their home’s floors were being refinished, Lisa had to move a giant cabinet filled with documents about Eamon – files about schools, doctors, diets, and the frantic search for answers.

“The papers were about a foot and a half thick,” she says, laughing. “I’m 55 now and I look back and think, ‘We had so much energy and drive back then.”

Lisa and Bob needed it as they went to battle for their son, shuttling from one doctor to the next, hoping for a diagnosis, lying in bed unable to sleep as they thought of Eamon’s future – or if their boy who so scared them when he zoned out during one of his fugues would even have much of one. After the diagnosis, they testified before Congress, gave interviews to journalists and organized celiac fundraisers. They couldn’t do enough to spread the word; it was also their way of saying ‘thank you’ to Dr. Peter Green.

“I still get e-mails and calls today from friends of friends or family who say their daughter or son was just diagnosed, and where do they go, what do they do?” says Lisa. “I list my resources and, if they’re in the New York area, I tell them to contact Peter Green at the Columbia Celiac Center. And I can reel off the top of my head companies that make great gluten-free products.”

The couple is proud of Eamon – just as they are of all their children. They want him to have four enjoyable years at college before real life intrudes, and they and their son did groundwork before he applied at any institution. They needed to be certain there were cafeteria protocols for students with celiac disease, and Eamon will meet the kitchen staff at the college he chooses to attend.

Eamon wanted to go somewhere smaller, such as University of Scranton in Pennsylvania or Ithaca College in upstate New York – places that are close to home and won’t be as overwhelming.

And whenever there’s the twinge that comes with the thought of their youngest leaving home, the Murphys think back to a gala that was held in New York City four years ago in honor of Eamon and the entire Murphy family for their efforts in organizing five fundraisers and spreading celiac disease awareness. Eamon was giving a keynote speech, which he wrote and stowed in the breast pocket of his dress jacket. But when he got up to the podium and reached for the speech, it was gone.

So he winged it. “My name is Eamon Murphy and I was diagnosed with celiac disease when I was 4,” he began. “Peter Green saved my life.” The audience gave him a standing ovation.

To read our original article about Eamon Murphy click here.

Photography by Debbie Miracolo