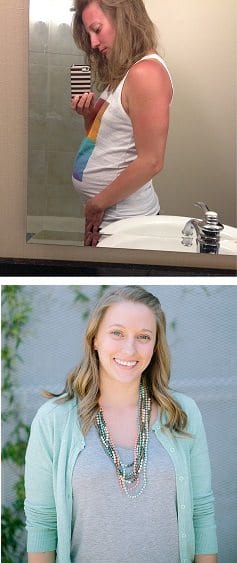

April Marlow-Ravelli (Top) showing effects of glutening at only one month pregnant. (Bottom): April two months later.

April Marlow-Ravelli (Top) showing effects of glutening at only one month pregnant. (Bottom): April two months later. For celiac patients, getting glutened is surprisingly common. Read all about it in this article from the Fall 2014 edition of Allergic Living magazine.

SHE looked down at her stomach in shock and disbelief. While April Marlow-Ravelli was one month pregnant, her belly was suddenly protruding as if she was six months along. Round and hard, her stomach was also in so much pain that she was having trouble breathing.

With this gut-wrenching discomfort, she knew exactly what had happened. “I’ve been glutened!” Marlow-Ravelli thought.

Earlier that day in May 2014, the fit 31-year-old had run the first five-kilometer leg in a relay marathon in Burlington, Vermont and then stayed to cheer on her teammates. By 1 p.m., she was starving and, once served at a local restaurant, she inhaled a salad and piece of salmon.

A resident of Durham, North Carolina, Marlow-Ravelli was diagnosed with celiac disease seven years ago, and has been careful ever since to avoid food with wheat, barley and rye – the gluten containing grains that for years had caused her migraines, bloating and diarrhea. In restaurants, she always explains her condition and asks servers a lot of menu questions.

That Sunday afternoon was no different, and the waiter had seemed well-informed. “You can’t have the chicken because it has a marinade, but you can have the salmon, no problem,” he assured. Except – he was wrong. It wasn’t the first time Marlow-Ravelli has been glutened, and she knows it won’t be the last. Aside from the physical smackdown, there is the disquieting knowledge that no matter how hard she tries, she cannot seem to steer clear enough of gluten to heal the damage it has done to her small intestine.

Study findings bolster what Marlow-Ravelli’s gut, quite literally, has been telling her. During the 2014 Digestive Disease Week conference in Chicago, Dr. Joseph Murray of the Mayo Clinic presented highly promising results with 342 celiac patients participating in a clinical trial of larazotide acetate, a novel drug that’s being evaluated as a support to the gluten-free diet for treating celiac disease. But while that was the good news, the bow-tied gastroenterologist also referenced research that shows an astonishing level of recurring symptoms in celiac patients on the gluten free diet.

“Up to 70 percent of individuals report being exposed to gluten deliberately or inadvertently, which causes not only GI-related symptoms, but also headache and tiredness,” Murray summarized to conference-goers. In addition, he and colleagues presented a poster about another study, which looked at symptoms and inflammation in patients with celiac disease. It found that 65 percent of participants had a level of intestinal damage consistent with untreated celiac disease, despite their attempts to follow a gluten-free diet.

While those with the condition express concern about persistent intestinal damage and whether it leaves them susceptible to serious diseases, such as lymphoma, from his Minnesota office, Murray adds this note of comfort: there is a big difference between “healing” and “being healed”. One Finnish study, in fact, concluded the latter may take up to nine years.

“Celiac disease heals from the bottom up and when I take a biopsy, I’m only taking a sample from the top six or eight inches,” he says. “Consider that there is about 20 feet of intestine coiled in the body and it’s easy to understand. That’s a lot of intestine that has to get better before we can call it healed.”

In celiac disease, the immune system attacks the lining of the small intestine when it detects the presence of gluten. This leads to symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, fatigue or even brain fog. In the person with undiagnosed celiac disease, the hair-like villi in the small intestine become damaged over time, and key nutrients won’t be absorbed. The longer term consequences can be a host of disparate conditions, from osteoporosis to infertility, and even cancer.

To manage the condition and your gluten-free diet, Murray thinks a key is to be closely monitored for at least the first few years, and to be honest with your physician. If you’ve consumed something with gluten, say so, not just what you think the doctor wants to hear. “I suspect some patients may not be telling the whole story about gluten exposure. They are likely getting some, at least intermittently,” he says.

Dining Gluten-Free: Tips and Where Gluten Can Hide

Before the most recent studies, there was only limited data on glutening based on results from pediatric patients. Dr. Daniel Leffler, a gastroenterologist at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School in Boston, makes an important observation on this: children heal more quickly than adults. Think of that bruise your child got the other day, which has disappeared by now, yet the one you developed a month ago is still slowly fading.

“It works the same way with celiac disease,” Leffler says. “There is a very strong correlation between older age of diagnosis and persistent damage on your biopsies.”

He counsels celiac patients to be, well, patient – given the tools at his disposal today, his focus is to help them feel better. He knows there is no such a thing as a perfect gluten-free diet, so regular blood work is important, as is keeping abreast of research.

“Gluten exposure is part of the reason for not healing but it isn’t the whole reason. This is a cause for concern and we need to learn more,” he says. “That said, the data are a little mixed but the best suggest the lifespan is not all that different between patients with persistent intestinal damage and those who heal.”

Next: The Science Behind Getting Glutened