From the Allergic Living magazine archives.

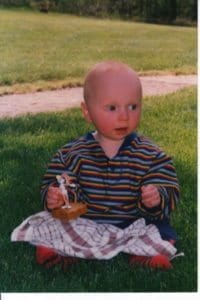

Eamon Murphy started out life as an elfin, silent toddler. At 3½ years of age, he began to fall into short trances without warning, his blue eyes unfocused and his mouth moving as if deep in conversation with someone unseen. When his mom called out to him, he wouldn’t respond.

Then all of a sudden, he’d snap out of it, as if nothing had happened.

As eerie as they were, these fugues were only the latest of a long list of symptoms that doctors could not explain. Eamon’s parents, Bob and Lisa Murphy, had first taken the boy to the pediatrician when he failed to meet infant developmental milestones, such as tracking movement with his eyes and sitting up. It would only get more worrisome.

When he began to eat solids, Eamon’s habit was to stuff his mouth so full of food, he’d spit much of it out unchewed. Then there were the accidents that twice left him a tiny figure swathed in white: a full plaster leg cast at 18 months after his two big brothers bumped against him in the kitchen, and a sling for a broken arm and cracked collarbone about a year later, when his sister pushed him down in the front yard.

“It was like every time Eamon fell, something would happen,” Lisa Murphy says. “It wasn’t like with our other kids.”

In the early going, the pediatrician assured the parents that the problems were because their son was an adored if passive fourth child, who just went with the flow as the rest of the family cared for him. Eventually, he’d catch up. So the parents waited, anxiously watching for signs of improvement.

Only there weren’t any. When Eamon still wasn’t speaking at the age of 2, he was declared “speech and language delayed.” That’s when Lisa Murphy demurred.

“You know, I have this weird condition called celiac disease,” she told the pediatrician. “Could it be that?”

She had been diagnosed four years before Eamon was born, while pregnant with her third child. It had been a long ordeal before the homemaker found out why she was always exhausted, why her hair was falling out and why she doubled over in pain when she ate something as small as a cookie.

Her family doctor at the time actually attributed her symptoms to stress – and recommended that Bob Murphy, a senior vice president at Citigroup Global Markets, take his wife out to dinner more often. When specialists finally found out she had celiac disease, Lisa read as much about it as she could.

She learned that her immune system saw gluten, a protein in wheat, barley and rye, as an intruder, and was responding by damaging tiny, finger-like projections in her small intestine that allow nutrients to be absorbed.

She became aware that the disease can lead to malnourishment, anemia and a host of problems, including osteoporosis, infertility and depression.

Once on a gluten-free diet, Lisa regained the energy to be a wife and mom – the unflappable center of an unruly, fun brood in the hamlet of Chappaqua, north of New York City.

Could her youngest child, who spat out food and broke bones like they were matchsticks, have the same disease?

But the pediatrician was adamant, broken bones and all. The boy’s mother was told: Eamon could not have celiac disease because if he did, he would have symptoms like a constantly bloated abdomen and diarrhea, and would be crying all the time.

Two years later, in 2000, Lisa Murphy’s world would be rocked when she attended a talk by Dr. Peter Green, the founder of the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University. The affable physician launched into a speech about how celiac disease can present itself in a myriad of ways, from bloating to seizures and anti-social behavior, and he noted the condition was hereditary.

He urged those diagnosed with celiac to get their family members tested. A light went off for Lisa. She called Bob and the couple agreed they should get their kids screened immediately.

Her eldest, Colin Murphy, who was then 11, turned out to be positive and already had developed osteoporosis in his spine and forearm.

And Eamon, whose fugues had so alarmed his family, was positive, too. At once angry over the misdiagnosis and hopeful, Lisa thought, “Maybe now, we’ve found the answer.”

About one per cent of the population in North America has celiac disease – a statistic that has already increased fourfold in the past 50 years and is only getting larger. Green says no one knows why.

Maybe it’s because gluten is present in so many more products, including lip balm and vitamins, or perhaps gluten itself has become more toxic, or there may be other environmental or dietary factors.

Next Page: Confusion Over Symptoms