From pitted tooth enamel to canker sores, oral health may be a sneaky sign of celiac disease. Yet too few dentists are filled in on the risks.

Courtney LaBatte watched as her son, Alden, tried his hardest not to twitch as the dentist checked his mouth. Her anxious middle child, who was 11 at the time, doesn’t like medical offices, or needles, or lights shining in his eyes. She’d assured him the appointment with Dr. Ted Malahias in Groton, Connecticut, would be over before he knew it. Then mid-appointment, the dentist asked out of the blue: “Has Alden ever been tested for celiac disease?”

LaBatte tried to remember what she’d heard of this: “Is it a digestive problem?” she asked.

Malahias explained that it’s much more – an autoimmune disease. Celiac disease is triggered when the body detects the presence of gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye products. Right now, the only way to treat the disease is to eliminate gluten from one’s diet.

The dentist gently prodded: “Has Alden ever experienced bloating? Anemia or joint pain? Did anyone else in the family have such symptoms?”

Malahias described what he was seeing “as more than having one ugly tooth.” He explained that with celiac disease, the patina of the enamel in all four quadrants of the mouth may be affected. Alden’s teeth and overall dental health were a clue that something else appeared to be going on.

His comments made sense to LaBatte, a job coach for the United Cerebral Palsy Association of Eastern Connecticut. Alden’s teeth are ridged and crowded, and shot through with shades of preternaturally white, yellow and gray, depending on how the light hits them. Despite his age, her son had to that point only lost four of his baby teeth. He also was small for his age – 4 feet, 9 inches, and short stature is common in children with celiac disease.

Malahias stressed that he was in no way suggesting Alden had celiac disease, but simply that it would be good to see an expert about the dental signs and to get him tested. She promised to make an appointment “as soon as possible.”

LaBatte left the office contemplating how her son, years earlier, had been diagnosed with ADHD but he stopped taking drugs for it two years ago, since they weren’t making a difference. She’d observed that gluten did appear to affect Alden; he became hyper when he ate gluten. She thought of the migraines that invariably followed this, and the vomiting.

Plus, she recalled the times her son came home from his elementary school with his fists clenched, trying not to cry. Alden has endured bullying related to his diminutive size and his teeth – even swearing never to smile again. At times, he has said he doesn’t want to go back to school. Other times, he wants to hurt the kids who treat him badly. LaBatte counsels Alden against that – it would make him no better than the bullies. But she has always intervened to put up the good fight for him, speaking to the principals, his teachers and counselors, looking for resolutions. The same held true here, too: if he had celiac disease, she wanted to know, and now.

Europe Leads on Dental Health and Celiac Disease

Once, it was thought that celiac disease was just a childhood condition that would go away. Now it’s recognized as part of a family of autoimmune diseases that includes rheumatoid arthritis, Type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

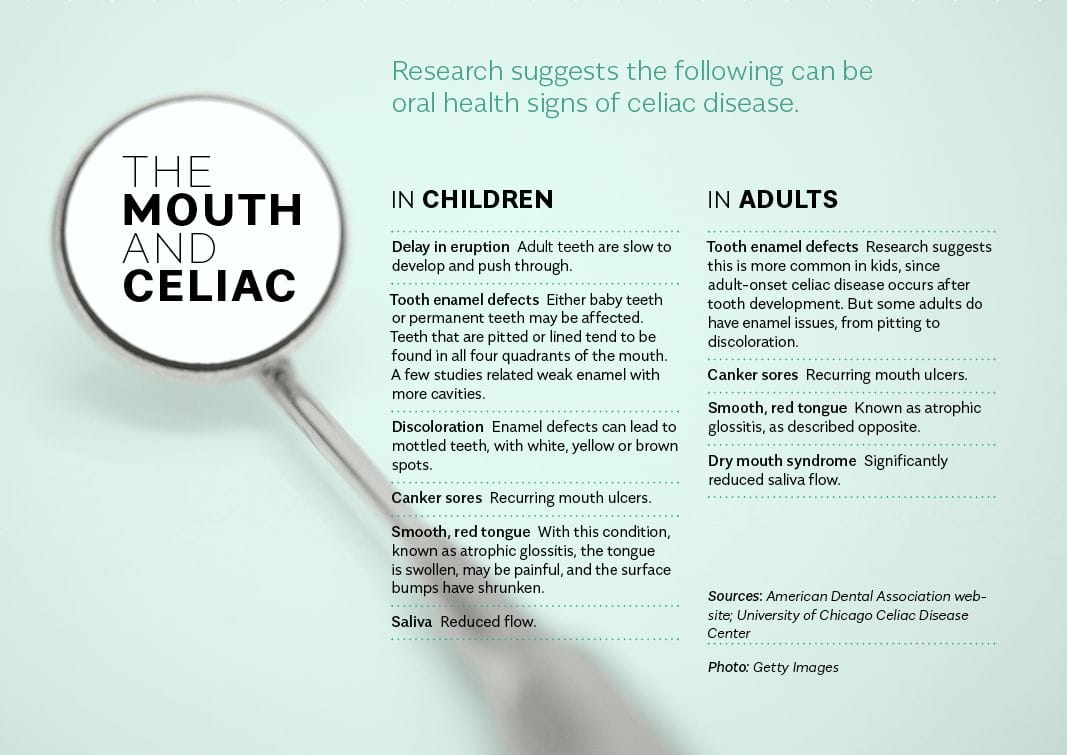

Today, research shows the disease’s symptoms have expanded beyond gastrointestinal distress to include an array of conditions that affect other areas of the body, from the skin to the bones, dental health and sometimes even the brain.

When someone with celiac disease consumes gluten, the immune system mounts a response that damages tiny projections called villi, which line the small intestine. The villi of the gut are essential to nutrient absorption. So it seems only logical that the mouth – the front door to the gut – would be affected, too.

Or so one would think. Canada became the first country to adopt clinical guidelines for dentists covering dental issues associated in celiac disease back in 2011. While U.S. celiac non-profits offer information about the relationship between the disease and dental health, the American Dental Association only recently published guidance related to celiac disease for its members.

As a result, Malahias says that most American dentists simply aren’t educated about the oral symptoms of celiac disease, and of the key role they could play in detecting it. He used to be one of them. It was only in 2006 that he became aware the condition could affect the development of tooth enamel when his wife, in her 40s, and his daughter, then 7, were both diagnosed with celiac disease.

“Our daughter’s gastroenterologist, who is from Europe, asked to see her teeth. Europe is way ahead of the U.S. when it comes to celiac research,” he says. “I went off to read as much as I could about it and found studies out of Italy and Finland, as far back as 1990. Then, I looked for people here who could answer my questions.”

The search led him to Dr. Peter Green, the gastroenterologist who heads up the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University. For years, Green has argued that U.S. health professionals need to become as informed of the condition’s diverse clinical presentations as their counterparts in Europe, in order to diagnose it more quickly and provide better support services.

Although one in every 133 people is estimated to have celiac disease, in North America it usually takes at least six years for someone to be diagnosed, a delay that can lead to myriad symptoms and increases the risk of developing other autoimmune disorders and even neurological problems.

“Medical and dental education, that is the issue,” Green tells Allergic Living. “Ask a dean at a dental school why it is not taught. It’s the same reason medical doctors don’t know about celiac disease. Their educators don’t know about it.” (Allergic Living did in fact ask the dean of Columbia’s school of dentistry about this. But messages to him went unanswered.)

Malahias teamed up with Green and other members of Green’s clinic to conduct the first-ever study of dental health defects and celiac disease in the United States. For the dentist, it was a passion project: he did the fieldwork in his office, in celiac support groups and at birthday parties, getting people to sign consent forms before asking them questions and having them pose for photographs with their mouths wide open. Then, he grouped the patients by age and gender, got another dentist he’d recruited to review the photos and delivered the raw data to Green at Columbia, where statisticians crunched the numbers.

Their findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology in 2010, linked celiac disease strongly to tooth enamel defects in children; 87 percent of the kids with the disease had these issues. Across all ages, there was also an association with recurrent aphthous ulcers, or canker sores.

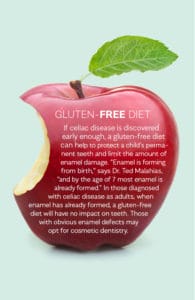

While there are other reasons for enamel damage – a bout with German measles, for example, or exposure to fluoride in a water supply – the researchers theorized that the defects appeared in childhood because celiac disease had set in when the enamel was forming and compromised the ability to absorb key minerals such as calcium, phosphate and vitamin D. Another hypothesis is that T lymphocytes, white blood cells central to the immune system, play a role in attacking enamel as it develops.

Another study, published in a November 2017 issue of the journal Nutrients, concluded that recurrent canker sores and enamel defects in adults are risk indicators that may suggest they have celiac disease. Then again, the authors cautioned that some of the tooth wear and other dental health issues could be related to factors such as bite problems, grinding and simply aging.

Getting Dentists Into the Loop

Adding to the medical evidence, a 2018 study from Brazil has found a significant relationship between the condition and dry mouth. Having a dry mouth contributes to tooth decay because there is no saliva to wash away food debris and plaque. As it happens, one cause of dry mouth is Sjogren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease that has been linked to celiac disease.

Malahias emphasizes that while the studies don’t provide black and white answers, they all underscore the importance of not forgetting about celiac disease when confronted with certain dental health symptoms; of keeping one’s mind open to the possibility. “The message we wanted to get out then – and we need to still get out now – was that if dentists could be part of the loop, it could save celiac patients years of suffering,” he says.

Sometimes, it isn’t easy. He recalls referring one patient, a 10-year-old girl with some telltale discoloration on her teeth, to her pediatrician with the suggestion she be tested for celiac disease. He got an irate phone call in response. “They wanted to see the articles I was referring to, as if I didn’t know what I was talking about as a dentist.” Malahias persisted, sending the articles in question. When the study came out, he received a note of congratulations from the once-doubtful pediatrician’s office.

It doesn’t matter to Malahias if patients such as that 10-year-old or Alden LaBatte have celiac disease but rather, that they see a doctor and get tested for it to find out. As this article was going to press, Alden was still undergoing screening. A blood test at his pediatrician’s office was inconclusive, yet the numbers were worrisome enough for Green’s team at the Columbia Celiac Disease Center to take a second look.

Courtney Labatte is eager to find answers. “A lot of people really don’t know exactly what is going on in their bodies for years – for my son, it has been almost 12 years,” she says. “It’s so important that you see a doctor or a dentist or any other health professional whom you trust, and who puts their 100 percent in to ensure that you’re as healthy as you can be.

“If it wasn’t for Dr. Malahias noticing these little details in Alden’s mouth, we’d probably still be casting around for answers,” she says. “Now, although we still may not know for sure, we are moving in the right direction.”

Related Reading:

Celiac in Children or Teens: the Sneaky Signs

Why You Don’t Want to Cut Out Gluten Before Celiac Testing

Celiac’s Evolution: The Mind-Boggling Rise of Non-Gut Symptoms